Sport in Mexico is a popular topic around the Center for Latin American Studies! Recently, we met Carina Carballo and learned about her journey from Mexico City to world traveler through her professional water polo career! Our latest feature is an interview Carina conducted with Professor David J. Wysocki-Quiros on his connection to Mexico and the complexities of sport and citizenship.

Professor Wysocki-Quiros is a lecturer in the Center for Latin American Studies at San Diego State University and the Universidad Autónoma de Baja California and a Ph.D. candidate in Latin American and World History at the University of Arizona, completing his dissertation titled “Exercising the Cosmic Race: Mexican Sporting Culture and Mestizo Citizens” on physical culture, race science, gender, and citizenship in modern Mexico. He has undergraduate and graduate teaching and research experience in Latin American, World and U.S. history, anthropology, religious studies, mixed methodologies, and economics.

What is your personal connection to Mexico?

I grew up in a predominately Mexican-American neighborhood in San Diego, attended bilingual courses in elementary school, visited the country often in different capacities, and always felt as if I lived in a truly bi-national region, so for me it was natural. Racism I witnessed and experienced as a child didn’t really sink-in until I was much older, but those experiences mixed with deeper understandings of inequality in the border region (sometimes even second-generation Mexican-Americans against newer and more indigenous looking migrants) made me want to study race, gender, power etc and explore cultural points of connection between Mexico and the US.

Tell me about your research project.

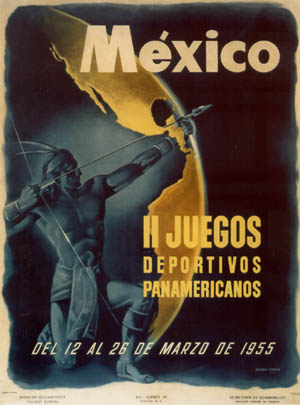

My project is titled “Exercising the Cosmic Race: Mexican Sporting Culture and Mestizo Citizens.” The project is a study on the government’s effort to forge a modern, virile, and whitened citizenry through the promotion of sports programs to the mostly indigenous masses from about 1900 to 1955 (the year Mexico hosted the Pan-Am Games for the first time—a prelude to the Olympics in 1968). Much of the history is institutional, exploring the politics of sporting bureaucracies and even the ways in which different arms of the government worked together to promote sports from different perspectives. Indeed, there were many. The military, medical, and pedagogical experts, especially during the revolution, all believed sports capable of transforming its purportedly backwards population into modern, disciplined, and healthy (moral) worker-citizens that revolutionary leaders deemed necessary for the modern world, but they did so from different philosophical positions/assumptions. Medical experts, for example, focused on the eugenic benefits of sports from a neo-Lamarkian perspective. Some essentially believed that by playing modern sports—those upper-class sports associated with the US or Europe—but not boxing or soccer typically—that participants could evolve into “supermen,” or at the very least whiten the population and reap the benefits that came with this. This is why the title includes the reference to Cosmic Race, based on the romantic novel from Jose Vasconcelos. Others in government simply promoted sports as a practical education that even indigenous communities actually wanted to participate in as the government struggled with literacy and Hispanization programs. They attached scientific and moral messages to sports programs, and some became enthusiastic followers, but many communities just tolerated these messages and played because the games brought rare excitement to communities.

Who are you working with on this project?

Just me 🙂

How did you become interested in doing a research project in Mexico?

I began this project as an MA student at SDSU. I did a project on baseball in the Oaxaca Valley because of the unique understandings/interpretations of the sport there. I intended to carry this over into my dissertation work but during the literary review I realized that the historiography of sports and physical culture in Mexico was very barren. So I did it. Some studies exist, but most are fairly superficial and none put together the story from multiple angles—especially military and eugenic importance of sport—so I aim to do this.

How long did you spend in Mexico and did you experience any culture shock?

The research comes out of two summers spent in Oaxaca, Mexico and eight months in Mexico City, in addition to travel many other places around the country and in the US. There’s always some culture shock when you travel somewhere new. Mexico City was difficult for me for a couple of weeks—heck, for the whole time in some ways. While I love culture and great food (things Mexico City is amazing for), I typically don’t like big, crammed cities. In Mexico City there were just so many people and always noise. So that was difficult. But transportation was amazing as were the people. The city itself is beautiful and so diverse from Xochimilco, to the Zocalo, to Coyoacan, to the Basilica etc etc. In Oaxaca, I’ve had some difficulties with getting water, experienced a very large earthquake that broke my windows and knocked me out of bed, and teacher strikes that blocked highways that made some work pretty difficult—things like this. But Oaxaca was very tranquil overall. I really have enjoyed my times there.

What was your favorite part about being in Mexico?

The food and the people. Easily. I lived in La Condesa in Mexico City, a very posh neighborhood, but with quick access to multiple markets, fine dining, and lots of al pastor tacos which I can never shake. Tijuana still has the best though. But I loved many things. The archives I visit were often in beautiful buildings draped in interesting murals or in colonial buildings or ex-monasteries/convents hundreds of years old. The AGN in Mexico City is actually located in the Carcel Lecumberri, a pan-opticon prison built in the time of Porfirio Diaz—also cells where many 1968 Tlatelolco students were held. I’m also thankful for the closeness to high mountains (I love to climb mountains and did a number of trips including into the Sierra Juarez in Oaxaca and climbed Iztaccíhuatl in Puebla (over 17,000 feet) with a friend of mine. I’ll also never forget my experience at Angangueo, Michoacán with the monarch butterflies. Truly a miracle of nature. All of these things were my favorite part. Also reading personal correspondences of Mexican national heroes, weaving together sometimes incredible stories, uncovering corruption and even detailing the butt-kissing…the whole thing felt a little gossipy and voyeuristic. Like I have a secret that nobody else knows. I guess this is part of the fun of being a historian.

What was your biggest challenge doing research in Mexico?

Challenges really abounded. Without being specific about certain archives or interviewees, you just have to remember that as a foreign researcher that your subjects are not always there to serve you. You will waste entire days sometimes waiting for certain materials that never arrive or are lost, sometimes people that you are counting on will seemingly drop off the face of the earth, and sometimes the archive itself may be inexplicably closed. There are many reasons for this and they vary depending on where you’re conducting the research in the country. But many people who work in archives are public functionaries and community volunteers with regular jobs and other life commitments. Their day to day life schedules will differ from yours often, and you just have to be prepared for a plan B, C, and D and be respectful and patient during the process.

As long as you’re a halfway capable, relatively self-sufficient human being then living in Mexico is not otherwise difficult. In Mexico City the subway is amazing in speed and cost. Although the cars get so packed that at times you will struggle to breathe and I’ve witnessed a number of groping incidents of women riders. Part of this is just the result of riding public transport in a city of 15 million people or more.

What do you feel when you think about Mexico?

Nostalgic.

What advice would you share with students interested in traveling to Mexico for research/tourism/etc?

Be respectful of people’s time and talk to anyone and everyone about your interests. Sometimes the trail goes cold and those conversations at cantinas, in taxis etc will lead you to look into exciting new stories, names, events, and much more. Plus, if you’re not out talking to people and doing things (and having a few mezcales), then what are you really trying to accomplish here? Lol

What is the thing you miss most about Mexico?

I miss my morning runs in the jacarandas at the ex-hippodrome in La Condesa and the natural spaces I was able to explore. There was also this organ grinder outside of the Biblioteca Lerdo de Tejada. Everyone seemed to loathe him, but for some reason I loved it.

What is the most surprising thing you learned when you visited Mexico?

How informed Mexicans are about US politics.

What are common misconceptions about Mexico?

The most common misconceptions are that when you’re in Mexico that bullets will be whizzing by your head constantly. Violence is real in some parts of the country, but many places are extremely safe.

Also, people in the US often think about Mexicans as a singular racial type and don’t understand that Mexico is one of the most diverse countries in the world. Even into the 1940s mass amounts of Mexicans didn’t speak Spanish and identified more with their patrias chicas than as Mexicans. There are, in other words, “Many Mexicos” and no one racial, ethnic, or stereo-type can encompass the enormity of its diversity.

Thanks, David, for this great interview. Want to learn even more and stay on top of news and events in Latin America? Follow Prof. Wysocki-Quiros on Twitter!